For those of you who are interested in fish identification books, or have spent many a happy (or confused) hour looking at taxonomic keys, this blog is for you. As an avid collector of fish books, I was delighted to hear that my friend and fellow fish fiend, Jack Perks was writing his own field guide to the fishes of Britain. In this blog I’ll be reviewing his latest publication, ‘Field Guide to British Fish’, and exploring the joys (and importance) of a good ID guide.

I’ve been collecting fish books since my early teens, and I used my time at university as an opportunity to ‘invest’ my student loan in as many fishy titles as I could. But it was only when I spent time aboard a fish surveying vessel, working on a photo ID guide for Plymouth Sound, that I truly appreciated the craft of designing a usable field guide. Many species, not just fish, are identified by characteristics that are very challenging to observe with the naked eye, or without spending considerable time looking at the specimen up close. Such subtle differences are captured in immense detail in taxonomic guides, which is perfect for lab work, but capturing these details in a field-friendly, accessible format is no small feat.

During some intertidal field work before I started my undergrad, one of my mentors said to me, “If you feel confident about a species ID, it means you don’t have a good enough book”. This made me laugh at the time, but I now realise he wasn’t joking! Misidentification is always a risk, so having the right guide is essential.

Despite collecting a range of taxonomic texts over the years, as an underwater photographer, I’ve always reached for field guides first and foremost. They help steer me through taxonomic resources or sometimes provide enough information to confirm an ID on their own. The combination of strong field photography and notes on features that are easy to spot during passing interactions has always excited me. In some (or if gobies are your thing, many) cases, you will not always be able to identify a species from a single interaction or photograph, but having the right book on hand greatly increases your chances.

For me, the gold standard for UK marine fish photo guides was set in 2009 by Paul Kay and Frances Dipper, with ‘A Field Guide to the Marine Fishes of Wales and Adjacent Waters’. The book combines excellent photography with clearly thought-out descriptions adapted from taxonomic keys. However, it’s scope does not cover freshwater fish.

So, when Jack told me he was working on a new photo ID guide, I was thrilled. I knew it would give freshwater fish the spotlight they so often miss and showcase their beauty through his outstanding portfolio of imagery. But the strength of this book also lies the depth of observation Jack has embedded into each page. It is clear after a page or two that Jack has spent countless hours observing fish behaviour, and that shines through. Field Guide to British Fish, is an outstanding addition to my collection, and I don’t saythis lightly. As is often the way in broader contexts, guides seldom give freshwater fish the time and attention they deserve. This book does the exact opposite.

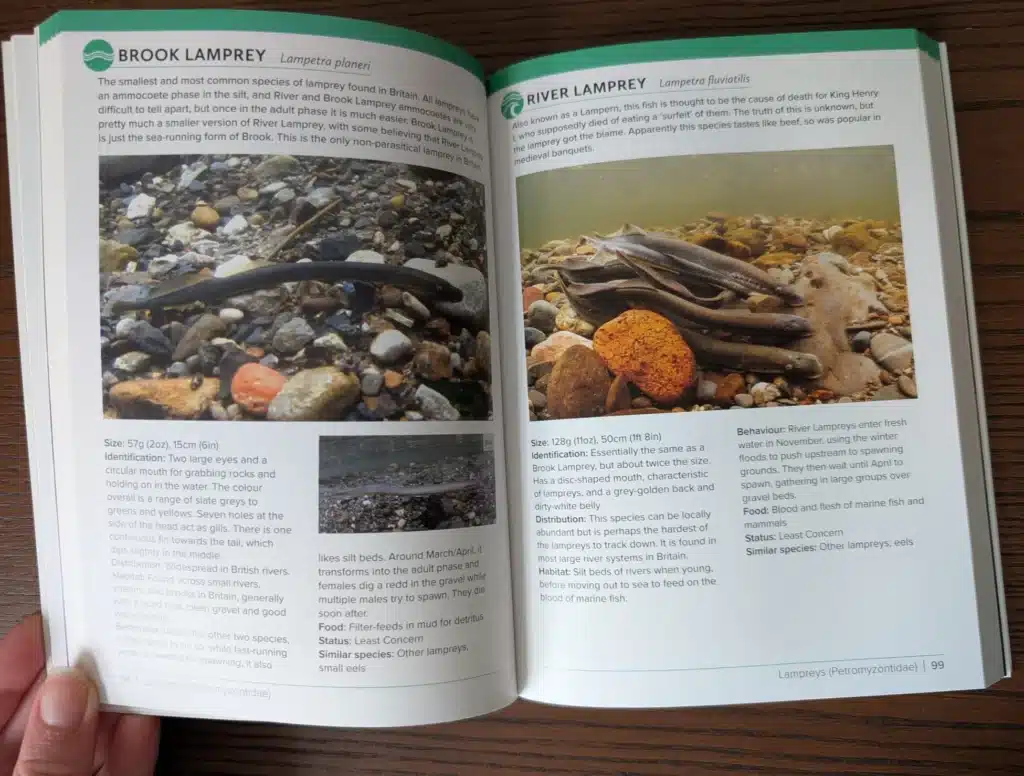

Field Guide to British Fishes is a 272 page love letter to Britain’s Fishes, and it contains everything you need to get started on your fish twitching journey. Each entry is accompanied by one or more images, descriptions of anatomy key to identification, behaviour, similar species, size, habitat, diet, and IUCN Status. Even if you’re not someone who plans to snorkel every weekend in the pursuit of spotting a new species, this guide will give you a comprehensive picture of the underappreciated diversity of fish in British waters.

Field ID guides, whether an Observers Book, or Collins Pocket Guide, have fed my inner child’s love for both natural history and artwork for many years, and so I’m inevitably excited by the addition of a new ID book for my favourite group of vertebrates. But beyond a nostalgic appreciation for a good ID guide, Jack’s book is the perfect combination of excellent artistry and fantastic identification insight.

Freshwater fish are chronically overlooked; they live quiet lives in shaded streams, gravel-bottomed rivers, and urban backwaters. They are rarely the stars of documentaries or conservation campaigns. That’s part of why Jack’s guide feels so important. It doesn’t just include freshwater fish, it celebrates them. It’s hard to protect what people don’t see, and even harder to love what you’ve never noticed. Guides like this help bridge that gap. They remind us that these fish are here, they’re remarkable, and they’re worth saving.

)

)

)

)