- The last time the Keli bladefin catfish (Encheloclarias kelioides) was seen was 1993, approximately 300 km from the site of this discovery.

- The finding extends the range of the species considerably, and highlights the importance of small remnant forest fragments as harbours for biodiversity.

- The discovery confirms the species as currently the only freshwater fish species in Singapore listed globally as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List.

Until recently…

…the air-breathing catfish (Encheloclarias kelioides) had only ever been seen and recorded twice: once way back in 1934, and again in 1993. With much of the species’ eastern Peninsular Malaysia peat swamp habitats having been drained to make way for palm oil plantations, the catfish was listed as Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct) in 1996. But in August 2022, researchers were baffled when a specimen turned up in a trap set by students researching crabs in Singapore’s Nee Soon Swamp Forest. Incredibly, it was the elusive Encheloclarias kelioides, discovered for the first time many miles from where it had previously been recorded.

Dr Tan Heok Hui, a Singaporean ichthyologist based at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, Faculty of Science, National University of Singapore, was one of the researchers who confirmed the identity of this surprising discovery. He said, “Encheloclarias has never been recorded in Singapore, and Encheloclarias kelioides is a really rare species that has previously only been recorded from peat swamp habitat. Singapore doesn’t have real peat swamp – the specimen was found in more like a mature acid swamp forest – so the discovery is pretty remarkable. It has rewritten our knowledge of Encheloclarias. When it first made its way to me, I thought, you’ve got to be kidding, this has to be a practical joke!”.

The Encheloclarias kelioides individuals caught were accidental bycatch from traps that had been set by Tan Zhi Wan, Research Assistant at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum and Elysia Toh, Research Associate at Yale-NUS College as part of their research into semi- terrestrial crabs. Nobody was actively looking for Encheloclarias, and it was just pure luck that they recognised them as being different from any catfish known from that region. They had no permit to take the fish from the Nee Soon reserve, but before they returned the individuals to the water, they took photos to send to the experts.

Dr Tan was one of the ichthyologists who received the photos…

…and he immediately recognised the images as being Encheloclarias. A month later, Dr Tan, Tan Zhi Wan and Elysia Toh visited the same area of the Nee Soon Swamp Forest where the individuals were previously found, set similar traps and left them overnight. When they checked the traps the next day, the fish was there. Dr Tan said, “It gave me the impression that we were really lucky”.

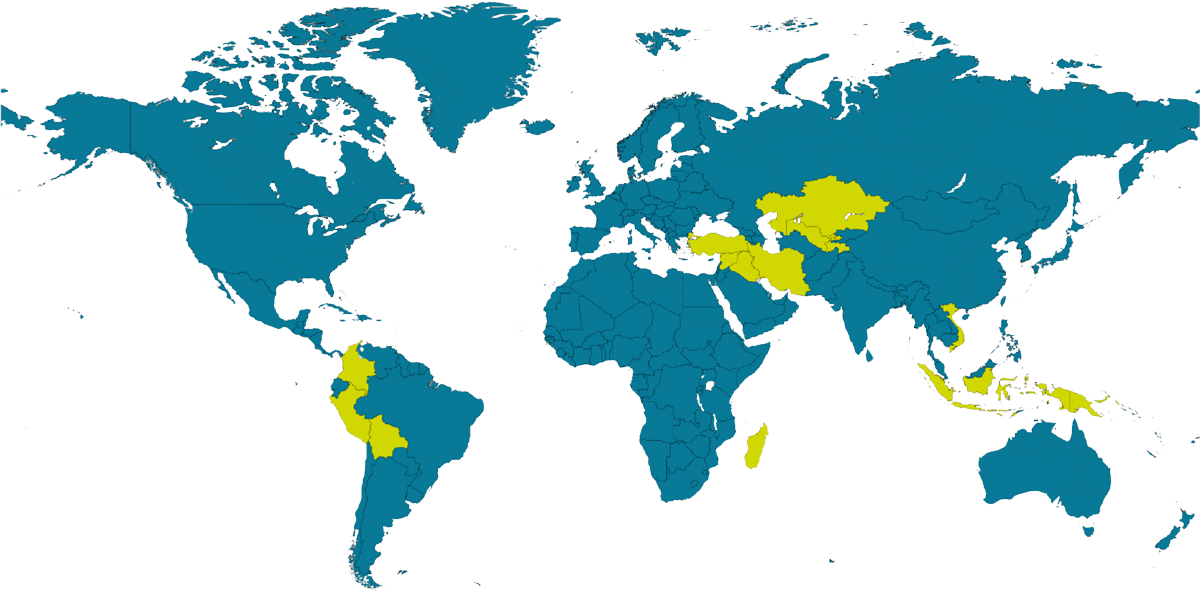

The discovery represents a range extension for the species, which was previously understood to be restricted to peat swamps in eastern Peninsular Malaysia and possibly central Sumatra (the specimen found there has not been confirmed as Encheloclarias kelioides) (Tan, Zhi Wan et al, 2023).

The Bebar drainage where the species was spotted…

…in 1993 is around 300 km from Nee Soon. So how did the species end up 300 km from where it was last seen three decades ago? Over many millennia, Tan said, “Southeast Asia experienced floodings and drying outs from rising and lowering of the sea level. The Gulf of Thailand actually once drained to one major river, and Singapore and part of Malaysia would have been part of that. They were once connected”.

Finding Encheloclarias kelioides in the Nee Soon Swamp Forest is significant for a number of reasons. Firstly, it proves that the species is not extinct. Secondly, this represents a range extension for the species of hundreds of kilometres. And thirdly, it helps confirm the Nee Soon Swamp Forest as an area of global conservation importance. While small, at approximately 5km 2 , it is the last remaining fragment of primary freshwater swamp forest in Singapore and is lush with biodiversity, harbouring more than half of the native freshwater fish species in Singapore, with some species being restricted only to this forest (Ho et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2020). Furthermore, it is protected under Singapore law: with the public needing a permit to enter and no threat of development, it has become a secure refuge for wildlife.

Given that species of the genus Encheloclarias are acid-water specialists, this discovery highlights the significance of the Nee Soon Swamp Forest and the importance of conserving this habitat as a stronghold of uncommon and stenotopic freshwater fauna in Singapore (Ng & Lim, 1992; Cai et al., 2018; Clews et al., 2018;).

According to Dr. Tan…

…to ensure Encheloclarias kelioides is protected from extinction, Singapore needs to keep doing what it has been doing, i.e. keep Nee Soon swamp protected. And there should be, “Proper baseline surveys and monitoring programmes by local experts, proper and fair legislation, and enforcements if people break the laws”.

He conceded that conserving the Encheloclarias genus could be a bit more tricky: “When wetlands are protected, they are never protected for the freshwater inhabitants but for birds mostly, and enigmatic animals like orangutans. Seldom fishes, which is sad. To get funding to do these surveys is not easy, and most of the local conservationists are not really trained to recognise the fish. Also, I’ve been to protected areas where you can catch fish and eat them. You can’t catch a bird or a mammal but there are different standards with fish, which is often viewed as a cheap source of protein”.

In light of the new discovery, Dr Tan together with the rest of the team, including Associate Professor Darren Yeo of the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum and Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, Dr Cai Yixiong, Senior Manager at the National Biodiversity Centre, National Parks Board (NParks), Tan Zhi Wan and Elysia Toh recommend the species’ IUCN Red List assessment status to be revised to Critically Endangered and consider its national conservation status in Singapore to be Critically Endangered.

The discovery occurred a few months before…

…the planned release of an ‘The Strategic Framework to Accelerate Urgent Conservation Action for ASAP Freshwater Fishes in Southeast Asia’, a collaboration between the IUCN Species Survival Commission Asian Species Action Partnership, SHOAL, and Mandai Nature, that provides a strategic framework to accelerate urgent conservation action for the most threatened freshwater fish species in Asia. The Strategic Framework is due for release this spring.

The study on the discovery of several specimens of Encheloclarias kelioides in Nee Soon Swamp Forest was co-authored by the National University of Singapore (NUS) and NParks, which is the lead agency for greenery, biodiversity conservation, and wildlife and animal health, welfare and management in Singapore, and responsible for enhancing and managing the urban ecosystems there.

In a statement…

Mr Ryan Lee, Group Director, National Biodiversity Centre, NParks, said, “The presence of these specimens in Nee Soon Swamp Forest within the Central Catchment Nature Reserve suggests the importance of small forest fragments as habitats for biodiversity including cryptic species. The Central Catchment Nature Reserve is one of four gazetted nature reserves in Singapore, which are legally protected areas of rich biodiversity that are representative sites of key indigenous ecosystems. Hence, there are restrictions on the activities that can be carried out in these areas, as well as access to certain sites, to safeguard the native flora and fauna.

“As such, minimal change to the existing freshwater swamp conditions are possible factors that could have allowed Encheloclarias kelioides to survive. It is reasonable to expect that more freshwater fish species may be discovered here in the future.

“NParks will continue to work with researchers to better understand the abundance and distribution range of Encheloclarias kelioides in Singapore, as well as the role these native catfish play in the freshwater ecosystem. This discovery highlights the significance of Nee Soon Swamp Forest as a stronghold of uncommon and specialised freshwater fauna in Singapore. As part of our efforts under the Nature Conservation Masterplan, NParks will continue to conserve Singapore’s key habitats, through the safeguarding and strengthening of Singapore’s core biodiversity areas, including our nature reserves. In addition, we will continue to conserve more native plant and animal species. These efforts will continue to allow our native biodiversity to thrive, allowing us to achieve our vision of becoming a City in Nature”.

The Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum is currently celebrating its eighth birthday, and Encheloclarias had been displayed in the museum as part of the anniversary celebrations.

The species does not currently have a common name. Dr Tan suggested it could be called the Keli bladefin catfish: bladefin catfish is the common name for all Encheloclarias, and in Malay, Clarias catfish are known as Ikan Keli.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)