Expedition Mahseer

On May 8, I travelled to southern India with a team of fish experts to scope out a joint project to save the hump-backed mahseer. The trip comes at the tail of a long story of conservation detective work of one of the world’s most charismatic fishes that has led us to take action, in the eleventh hour, to save a critically-endangered fish before it disappears forever. Mike Baltzer, Executive Director of Shoal, reports from a project scoping trip to southern India.

There are some creatures that have inspired and awed people through the ages. Some real animals like lions, tigers and elephants and some legendary like dragons or the unicorn. The mahseer (Tor spp.), a genus of very large, often beautiful and powerful fishes found in South and south-east Asia, fall right between the two. Mahseer are a real animal that has reached legendary status.

Often referred to as the “tiger of the river”, mahseers have been revered by the Indus Valley civilisation for more than 3000 years, worshipped by Buddhists and Hindus and treasured by local communities throughout the region. More recently, their fame has been maintained by featuring as one of the great icons of wild river angling – and it was this angling that has helped propel a species into conservation limelight.

For many years, anglers have yearned to fish for mahseer. Many stories and books have been written on the wonders of fishing for mahseer and the ultimate target, the holy grail of mahseer fishing, is the largest of the mahseers, the hump-backed mahseer.

The story of the hump-back has its own twist in its tail. Hump-backs are only found in the Cauvery River system in southern India and were first popularised in the late 19th century by British officers who considered mahseer angling to present a superior sporting challenge to shooting big game. Following Indian independence in 1946, many believed the mahseer had gone extinct, until a new era of conservation minded catch-and-release anglers (including Jeremy Wade of River Monsters fame) proved the fish was still extant and reignited a global interest in mahseer fishing in the late 1970’s. This drove the establishment of a recreational fishery, where the income from international anglers was used to employ local villagers as angling guides, drivers, bait makers and cooks. This quickly led to the realisation that local livelihoods now relied on the mahseer and that a live mahseer had a renewable value over a dead fish. Accordingly, whole communities started protecting this river from the poachers who often used highly destructive fishing methods (such as dynamite!).

In 2010 Adrian Pinder, a fisheries scientist from Bournemouth University and Director of the Mahseer Trust, took a curious and thankfully scientific look at the detailed records of the daily catch. In the records, together with the photos taken by the proud anglers, he noticed that there were two types of fish recorded, one with blue fins and the other with orange fins. He also noticed that overtime the larger orange-finned fish was declining while the blue-finned version was increasing. Could it be that these two were separate species and that one was beginning to push the other out? Pinder set off to find out and in 2018 he presented the results of his detective work which afforded the hump-back mahseer its first valid scientific name allowing the species formal recognition and qualification for conservation status assessment. In November 2018 the hump-backed mahseer was assessed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Without action, Pinder and his colleagues concluded, the hump-backed would be lost in our generation

What Pinder and his colleagues including southern India’s most respected fish taxonomist Dr Rajeev Raghavan discovered, was that the “blue-finned” mahseer had originated from a single hatchery and had been released into the Cauvery river basin in an attempt to conserve this species. Now the dominant mahseer species throughout much of South India, including the Cauvery, the fish had not only established, but become highly invasive – outcompeting the hump-backed mahseer for resources and pushing it towards extinction. It was only a dam (so often the scourge of fish populations) that had stopped the blue-fins from spreadinginto the final refuge of the hump-backed mahseer. There was therefore a chance to save it before it was too late. In late 2018, Pinder approached me and Shoal to suggest that we help the Mahseer Trust and others establish a project to save the hump-backed mahseer.

The last refuge of the hump-backed mahseer is found in the Moyar River one of the tributaries of the Cauvery and is confined to the stretch upstream of the Bhavanisagar dam. The Moyar River is set in the stunningly beautiful location of the Nilgiri mountains. It is famous for its outstanding gorge and the wealth of its wildlife. The area is home to one of the largest remaining populations of Asian elephant and falls between three highly important tiger reserves. The Moyar Valley itself has witnessed a remarkable recovery of its tiger population in the last ten years.

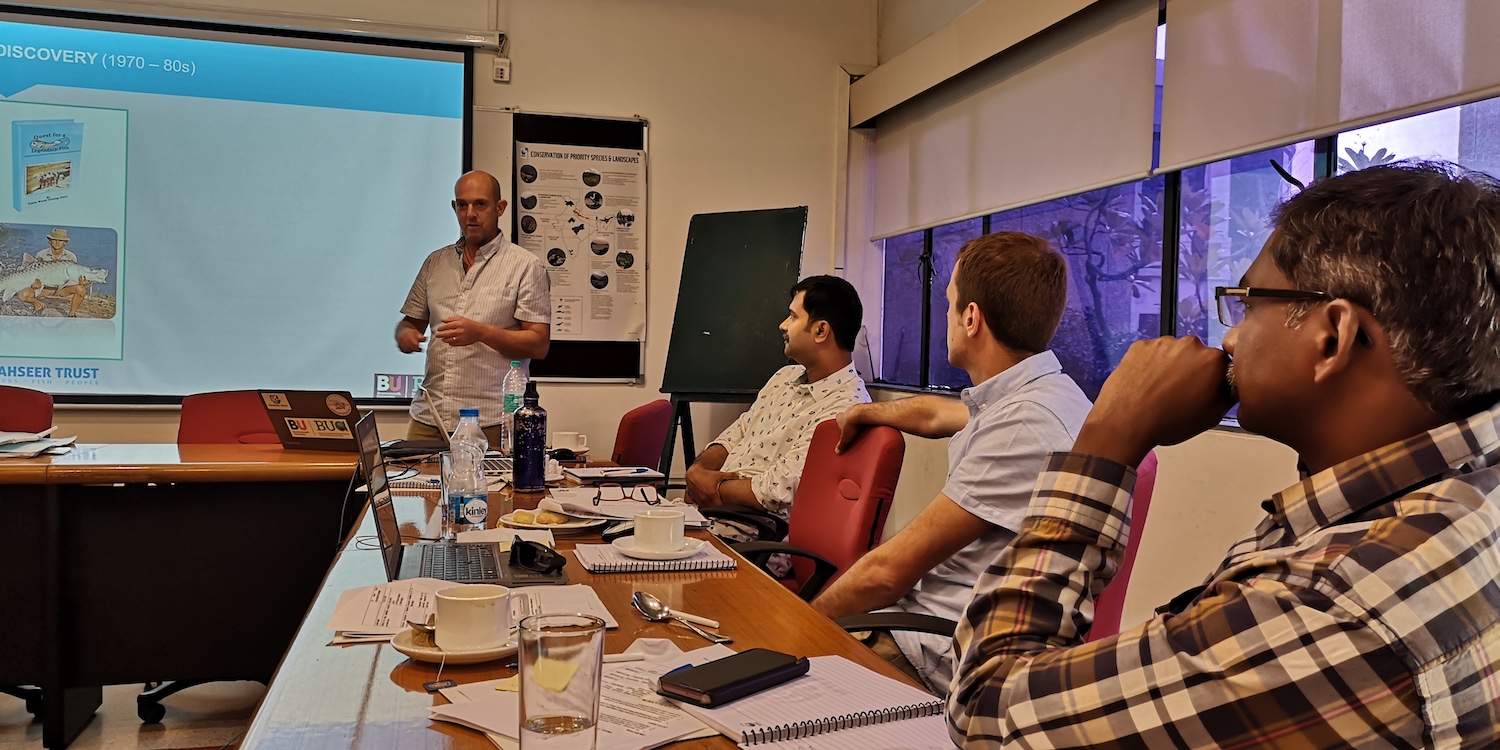

The trip this May was to establish the location and the research strategy for the project. The first stage of the project is to gather, as fast as possible, information on the status, distribution, ecology and most important, the breeding cycle of the hump-backed mahseer. While for many fish species this would be a straight forward exercise, our project scoping trip has shown that it certainly will not be easy for this fish. The project will require access to some of the most inaccessible areas in Asia and once there, the field teams will need to deal with the daily threat from tigers, elephants, leopards, sloth bears and crocodiles.

The initial work will require tracking the movements of the mahseer using bio- telemetry. This will involve inserting transmitting tags into individual fish and placing receiver stations at strategic locations along the river, extending into the unexplored and mysterious Moyar Gorge. This work will be led by the Mahseer Trust, Bournemouth University (UK), the Wildlife Institute of India and Kochi University Fisheries and Ocean Studies (KUFOS). In addition to the ecological research, the status of the environmental conditions such as water flow and pollution levels will be monitored. The project will also need to make the first steps towards preparing local community support, potentially involving WWF and Lively Waters. Once the team has better knowledge about the fish and the opportunities and threats to its conservation, a recovery plan, potentially centred on assisted breeding and reintroduction will be put in place.

Shoal’s role in the project is to help secure the funds to undertake this vital project. We will begin fundraising immediately and aim to start the project in November.

If you would like to support the project contact: mike@shoalconservation.org